When eggs hit $8 a dozen and the rent is too damn high, it's natural to feel like someone's gouging you. Politicians and activists often advocate for interventions like rent controls or price caps to force prices down. Yet this impulse, though understandable, reflects a fundamental misunderstanding of what prices represent.

Think of this as a debate between two perspectives. "Signalists" see every price as a data packet—an ever-updating readout of supply and demand. "Price-Fighters," however, see price increases as evidence of exploitation or profiteering. This essay will illustrate why I believe the Signalist perspective is more effective at explaining the empirical evidence and guiding public policy.

The Price-Fighter approach, though well-intentioned, mistakes prices for villains rather than messengers. Prices don't reflect “inherent value” in items themselves but rather indicate the competitive context: what people are willing to pay. They’re messengers conveying information about countless individual decisions and signaling essential information about scarcity and abundance. Suppressing these signals, rather than addressing their underlying causes, often unintentionally exacerbates the very problems these interventions aim to solve.

The Nature of Prices as Signals

Consider the market for nickel. Imagine someone discovers a new battery technology that relies on nickel. This creates new demand for nickel. But how will miners and refiners know to increase production? It’s not because they subscribe to "Battery Technology Weekly". It’s because they see buyers willing to pay higher prices, and they respond accordingly. High prices incentivize miners to open new mines, encourage refiners to improve processes, and prompt manufacturers to seek alternative materials.

When prices increase, the Price-Fighter response is to impose controls. But this misunderstands the role of prices. Letting the market react addresses the root causes rather than the symptoms. Price controls, on the other hand, merely silence the message without addressing the underlying issue. If the government artificially caps the price of nickel, miners won't have enough incentive to find new deposits, and manufacturers won’t feel urgency to find substitutes. Eventually, shortages worsen because the market isn’t receiving accurate signals about the actual situation.

This is what prices do. They convey information. Similarly, when geologists discover a major nickel deposit, suddenly, we realize we have more nickel than we thought—manufacturers can start using nickel in more components. But how will they learn of this? Again, they don’t learn directly. Instead, the new supply information reaches manufacturers through declining prices, prompting them to recalibrate their production decisions. No central authority orchestrates this dance of supply and demand—prices do the work automatically, aggregating complex information from millions of independent actors across the globe.

As Nobel Prize-winning economist F.A. Hayek observed, 'We must look at the price system as such a mechanism for communicating information if we want to understand its real function.'

It’s an incredible feat when you think of it. No single person has comprehensive knowledge of every nickel mine, refinery, or stockpile worldwide, nor can anyone know every potential use and its importance. Yet, through the market, each of us can influence the price slightly based on our own limited information. In this way, prices aggregate all available knowledge from around the globe. Prices in a market economy serve as the most sophisticated information processing system the world has ever known.

Practical Applications

Most people don’t care too much about the price of nickel, but that’s why it’s a good place to get started. But let’s apply these same principles to areas people care about deeply—housing, energy, and insurance.1

Housing

This same principle applies to housing markets. When rents spike in a city, the Price-Fighters say, “Prices have gotten too high and people can’t pay rent. We’re not going to stand by and let this profiteering happen. Let’s freeze the prices.”

But the Signalists say this surge isn't arbitrary profiteering—it's valuable data indicating that demand for housing outstrips supply in that location. The price is simply delivering this message. The Signalist says that if politicians want to reduce the price of housing, they need to focus on the costs, not the price. A price is a communication tool—it conveys information about supply and demand. A cost is the actual resource investment required to produce something. If the goal is genuinely to lower costs, the solution isn’t to suppress prices artificially. Instead, it's to address the true underlying factors: streamline regulations, simplify permit processes, or find more efficient construction methods.

Instead, Price-Fighters attack the messenger—prices—by proposing solutions like rent control. However, rent control targets the price signal rather than addressing the underlying shortage. Capping rents doesn't create more housing or reduce the number of people wanting to live in an area. Instead, it distorts the market's information system. Developers, seeing they can't charge market rates, build fewer apartments. Existing landlords, unable to raise rents, defer maintenance. The housing shortage actually worsens, but now the price signal that would warn us about this growing scarcity has been muted, and the problem grows.

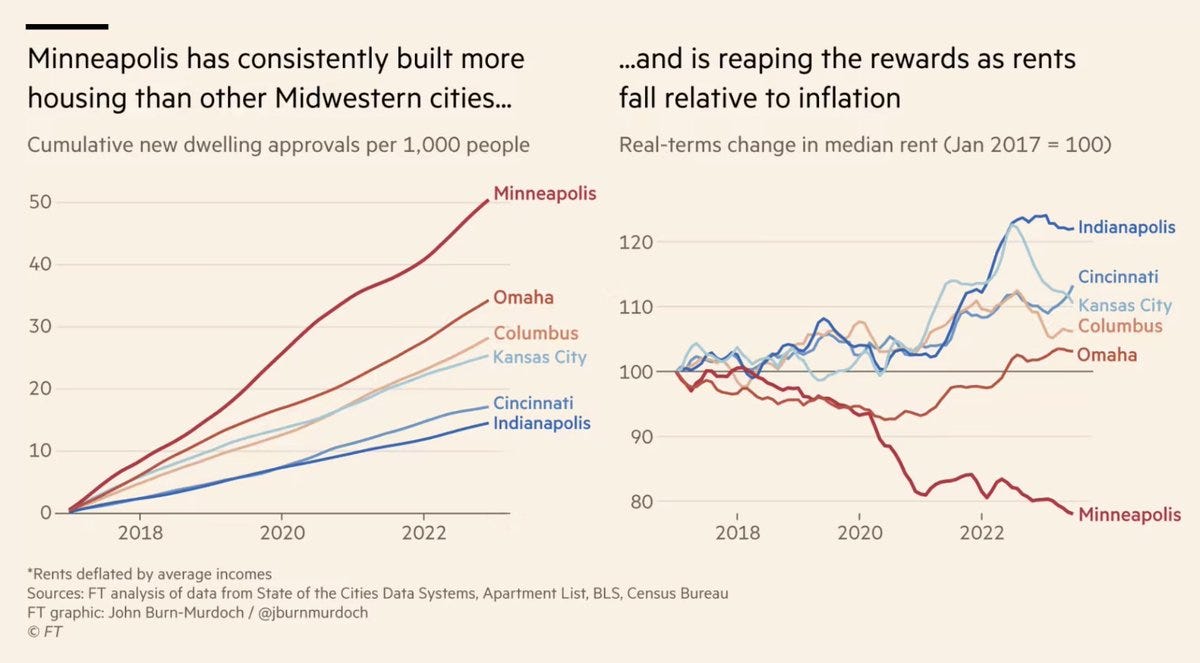

Minneapolis offers a clear example of how effectively cities can respond to price signals. When rents began rising sharply, the city didn't turn to rent control or impose additional regulations. Instead, it recognized the underlying message—housing was in short supply—and tackled the shortage directly. Minneapolis introduced housing reforms such as eliminating single-family zoning and removing mandatory parking minimums. As a result, construction increased significantly, and rents subsequently began to fall.

I’ve talked about housing costs and rent control before, so I won’t belabor the point. But it’s astonishing how often I come across this same phenomenon. Just this year, Zillow found that Denver, a city that has focused on building more housing, led the US in apartment cost decline. The same approach even worked in regulation-heavy Berkeley.

It wasn’t fighting the price through regulation that did it, it was understanding the signal it conveys and responding accordingly.

In California, the approach to housing has been counterproductive: restrictive regulations make building incredibly difficult and expensive—construction costs over twice as much as in Texas—while subsidies attempt to offset these high prices. But when you understand that prices are information carriers, you realize this approach is fundamentally flawed. By making housing nearly impossible to build, California drives up costs at the source. Then, by subsidizing those inflated costs, it suppresses the very price signals that would normally prompt solutions like regulatory reform or increased construction.

Sometimes we forget that an object's price isn’t an inherent property of the item—that a house valued at $1,000,000 doesn’t possess some intrinsic “million-dollar” quality justifying that price. Consider this scenario: the average home price is $1,000,000, and policymakers decide to help by giving everyone $10,000 towards buying a house. If prices were intrinsic, everyone would be $10,000 closer to homeownership, yay! But prices reflect competitive bidding. With more money chasing the same homes, sellers quickly realize they can charge $10,000 more. The price has shifted, but nothing inherent to the homes has changed—only the amount buyers can and will pay.

Thus, when policymakers treat prices as fixed obstacles rather than dynamic signals, interventions meant to lower costs end up making housing less affordable. The result is a handout to current homeowners (because their houses are now “worth” $10,000 more) at the expense of prospective buyers2—exactly the opposite of the intended effect.

This might sound like nonsense, but this is a real thing that actually happens. Research on low-income housing subsidies found that low-income vouchers have “caused a $8.2 billion increase in the total rent paid by low-income non-recipients, while only providing a subsidy of $5.8 billion to recipients, resulting in a net loss of $2.4 billion to low-income households.” That is, the exact people this program was designed to help ended up paying more, and the root cause is a misconception of how prices work.

Energy

Unlike most consumer markets, retail electricity is delivered through regulated local monopolies—households typically can't choose a competing supplier—so many free-market assumptions don't apply. In monopoly settings, prices can't fully function as information signals since there's no competitive market to generate them. However, we can still see the Signalist versus Price-Fighter battle play out in energy pricing debates.

One common proposal—pushed mainly by the Signalists—is time-of-use (TOU) energy pricing, wherein the price of electricity varies throughout the day based on energy availability. This allows the price of electricity to be used to communicate how much stress is on the grid. If energy is abundant (e.g., the sun is shining in a place with a lot of solar panels) and usage is low, the prices are low; but if the grid is maxed out, prices are high.3

I’m a big fan of this approach. Instead of me guessing, “It’s windy today. I bet the local wind farm is doing well right now, so I’ll start the dishwasher”, the electric companies can pass this information along to me in the form of a price. If my need is time-sensitive, I do it anyway. But over time and on the margin, people adapt. People get used to seeing high prices during the evenings and so choose to charge their electric vehicles overnight. The result is lower peak consumption, a more balanced grid, and a more efficient system—a win for everyone.

But despite its benefits, TOU pricing often faces opposition. California has a consumer advocacy group called The Utility Reform Network (TURN) that always opposes efforts to implement TOU pricing. They claim that it's exploitative and unfair for vulnerable populations who rely on electricity. Similarly, the AARP advocates against it, saying that it will hurt those on low incomes. However, this perspective misunderstands the true nature of these price signals. Time-of-use pricing isn’t about exploitation—it's about efficiently informing consumers when energy is abundant or scarce.

Consumer advocates should be pushing for these things. Consumers need to know this information. Transparent pricing helps everyone, especially low-income households, by making energy use more efficient, stabilizing the grid, and ultimately lowering system-wide costs. Inefficient systems hurt vulnerable populations most, as they inevitably lead to higher energy prices. UtilityDive4 reports that “Pilot programs have shown smartly designed residential time-of-use (TOU) and other time varying rate structures can effectively shift power consumption away from peak demand and drive significant savings for both customers and utilities.”

Insurance

Insurance markets are another example of the faceoff between Signalists and Price-Fighters. To a Signalist, when an insurance premium rises, it’s a signal that the amount of risk in that area has increased. In coastal Florida or the wildfire‑prone canyons of California, prices have soared because storms and flames strike more often and rebuilding costs more. A premium spike is a bright red flag: this site is dangerous and expensive to protect.

For the Signalist camp, that message is invaluable. Homeowners can heed it by elevating houses, installing fire‑hardening retrofits, or—if the number is eye‑watering enough—choosing a safer ZIP code. Local governments can respond by steering new builds inland, tightening building codes, or investing in levees and fuel breaks. The market doesn’t forbid living near the water; it simply presents the true cost.

The Price-Fighter camp takes the opposite approach. When private insurers abandon extreme-risk properties, Price-Fighters lobby for subsidies and government-backed insurance programs. The U.S. National Flood Insurance Program is the poster child. Under political pressure to maintain "affordable" premiums, it charged below-market rates for decades, resulting in classic moral hazard: homeowners repeatedly rebuilt properties in high-risk locations, knowing taxpayers would cover the costs.

Insurance premiums reflect the actual price of risk. Artificially suppressing premiums distorts incentives, encouraging reckless behavior. A vivid illustration of this is offered by John Stossel in Confessions of a Welfare Queen: How Rich Bastards Like Me Rip Off Taxpayers for Millions of Dollars:

In 1980 I built a wonderful beach house. Four bedrooms—every room with a view of the Atlantic Ocean.

It was an absurd place to build, right on the edge of the ocean. All that stood between my house and ruin was a hundred feet of sand. My father told me: "Don't do it; it's too risky. No one should build so close to an ocean."

But I built anyway.

Why? As my eager-for-the-business architect said, "Why not? If the ocean destroys your house, the government will pay for a new one."

[...]

If the ocean took my house, Uncle Sam would pay to replace it under the National Flood Insurance Program. Since private insurers weren't dumb enough to sell cheap insurance to people who built on the edges of oceans or rivers, Congress decided the government should step in and do it. So if the ocean ate what I built, I could rebuild and rebuild again and again—there was no limit to the number of claims on the same property in the same location—up to a maximum of $250,000 per house per flood. And you taxpayers would pay for it.

Florida has an ongoing debate around its Citizens Property Insurance Corporation, which is a nonprofit created to provide insurance for homeowners that private insurance won’t cover. Price-Fighters support this kind of thing: “If companies won’t provide insurance, the government has got to step in.” Signalists, on the other hand, oppose it: “Companies won’t insure these properties because the locations are too risky. Why are we subsidizing people to live in places where their houses are likely to be destroyed? They are charging 55% below sound actuarial levels. That means when the hurricanes come and knock down these houses, which they inevitably will at some point, other Florida residents will have to foot the bill. All so people can live somewhere it doesn’t make sense to live.”

And thus, the endless tug-of-war between Signalists and Price-Fighters continues, ensuring bloggers everywhere something to type about.

Working with the Market

Getting mad at high prices for housing makes about as much sense as getting mad at a fire alarm for telling you your house is burning down. The price is not the underlying problem, it's merely an indicator of where the real issues lie. As a Signalist, I believe the goal shouldn’t be to override these signals but to help people respond to them effectively. When we treat prices as signals rather than enemies, we can craft solutions that work with market forces rather than against them.

This doesn’t mean we must rule out all forms of market intervention. There are legitimate “gray-zone” situations—like natural disasters or sudden infrastructure failures—where temporary anti-gouging measures or rent-increase caps can prevent immediate harm and buy crucial time while the market adjusts. For example, imposing temporary price limits during a sudden natural-gas pipeline disruption can stabilize essential services long enough for broader responses to develop. Similarly, given the high transaction costs and logistical challenges of relocating to a new home, carefully designed regulations that limit abrupt, steep rent hikes might be justified.

Signalist thinking is hardly laissez-faire fatalism. We don’t need to throw people out of their homes, turn off their electricity, or cancel their insurance. None of this means that we can’t help those in need, just that we need to do it the right way. It starts by asking What is this price trying to tell us? and ends by fixing the bottleneck the price revealed, not by gagging the messenger. That approach may lack the visceral thrill of railing against “greed,” but facing prices squarely is the only path to durable, real-world solutions.

And for people who only care about sheep, there’s this.

Indirectly, through inflation or debt. Intuitively, though, it makes sense that the government can’t pass a law that makes everyone $10,000 richer.

In practice, there are pre-defined peak windows (typically late afternoon and early evening) and off-peak windows (at night), though it could also be done dynamically. The same principles apply either way, one just relies on expected demand rather than actual demand.

I don’t know this source well, and I didn’t look into the pilot programs, so I don’t know how much weight to put on this. However, MediaBiasFactCheck gets them a rating of “least biased” with a “high” factual reporting rating.