The Perils of Well-Intentioned Policies

How Rent Control and Other Zombie Ideas Harm Those They Aim to Help

The road to hell, as the saying goes, is paved with good intentions. Nowhere is this more evident than in the realm of public policy, where well-meaning initiatives can lead to disastrous results. Rent control is a prime example of this. Despite the near-unanimous consensus among economists and the wealth of real-world evidence demonstrating its negative consequences, rent control persists in many cities worldwide. This essay explores the phenomenon of “zombie ideas”—ideas that persist despite a history of failure—using rent control as a case study.

Rent control is often touted as a simple solution to the problem of rising housing costs, particularly for low-income renters. On the surface, it seems like a no-brainer: if rents are too high, why not simply pass a law saying they can’t be? However, this seemingly intuitive policy has a track record of unintended consequences that often leave the very people it aims to help worse off in the long run.

Rent control has become a textbook example of unintended consequences. The economic principles behind its failure are fairly simple: when a price ceiling is imposed on a good or service, such as housing, it artificially suppresses prices below the equilibrium point where quantity supplied and quantity demanded meet. This leads to a shortage, as the reduced prices stimulate an increase in quantity demanded while simultaneously disincentivizing suppliers from providing more of the good or service. In the case of rent control, this means that the policy actually reduces the quantity supplied of rental housing, exacerbating the very problem it was meant to address.

Economists have long warned about the negative effects of rent control. In 1971, the Swedish economist Assar Lindbeck famously quipped, "Next to bombing, rent control seems in many cases to be the most efficient technique so far known for destroying cities."

While not every real-world scenario plays out exactly as economic models predict, rent control seems to be a case where theory and practice align. In the textbook, Basic Economics, economist Thomas Sowell notes that "rent control laws have led to a very similar set of consequences in Cairo, Hong Kong, Stockholm, Melbourne, and New York." Despite the vast differences among these cities in terms of their history, politics, and social norms, rent control has led to remarkably similar outcomes: housing shortages, reduced quality of available units, and the emergence of black markets.

The consensus among economists against rent control is overwhelming. In a 2000 article, economist Paul Krugman described the effects of rent control as "among the best-understood issues in all of economics, and—among economists, anyway—one of the least controversial." This is no small feat in a field known for its wildly diverging opinions.

The University of Chicago's Booth School of Business regularly surveys top economists on various policy questions. In 2012, they posed the following question: “Local ordinances that limit rent increases for some rental housing units, such as in New York and San Francisco, have had a positive impact over the past three decades on the amount and quality of broadly affordable rental housing in cities that have used them.” The response was one of resounding disagreement.

I don't want to turn this essay into a treatise on rent control, so I’ll mention that there’s always more debate to have and you can read this Vox article to hear a dissenting opinion. Sometimes, rent control is proposed in tandem with other laws that seek to mitigate the unintended consequences. But if you’re going to side with that Vox article, I would note that the book Rent Control: Myths & Realities, with contributions from Nobel laureates Milton Friedman and F.A. Hayek, contains yet more evidence that the policy is harmful to those it’s trying to help.

Yet, despite near-unanimous opposition from economists, rent control policies persist in many cities, inflicting harm on their communities. An article titled “Rent Control: Do Economists Agree?” stated that “the literature on the whole may be fairly said to show that rent control is bad, yet as of 2001, about 140 jurisdictions persist in some form of the intervention.”

Ireland

For example, Ireland passed rent control measures in 2016. An article in the Irish Times discusses the recent efforts there:

Government measures to control rents have backfired and in many cases have led to an increase in rents, a new report has claimed.

The study by economist Jim Power suggests that rent pressure zones (RPZs), introduced in 2016 to limit rent price increases, have resulted in significant "rent rigidities" and an inefficient two-tier system where the proper maintenance of rental properties is no longer economically viable.

This has prompted many smaller landlords to exit the market and to be replaced by institutional landlords with new stock at higher rents.

A long-standing complaint against the RPZ system is that new rental properties or tenancies are excluded from the restrictions and can be put on the market at any rent. “The real losers are tenants at the lower end of the market,” Mr Power said.

The report […] concludes that the Irish rental market is not functioning in an effective manner, and that RPZs are undermining the market and not achieving what they are intended to achieve.

A few months later, Sky News ran the headline, “Young people in Ireland face 'terrifying' rent crisis due to chronic housing shortage”. The article is a good reminder that these are not mere academic exercises or abstract policy debates. Rent control policies have real, devastating impacts on the lives of individuals and families who are left to bear the brunt of the unintended consequences. From the article:

In the west of the city, 22-year-old Courtney Doyle has finally secured an apartment for her and [her] partner Ross, after spending the last five years sleeping on friends' sofas. It was urgently needed, as she is now six months pregnant.

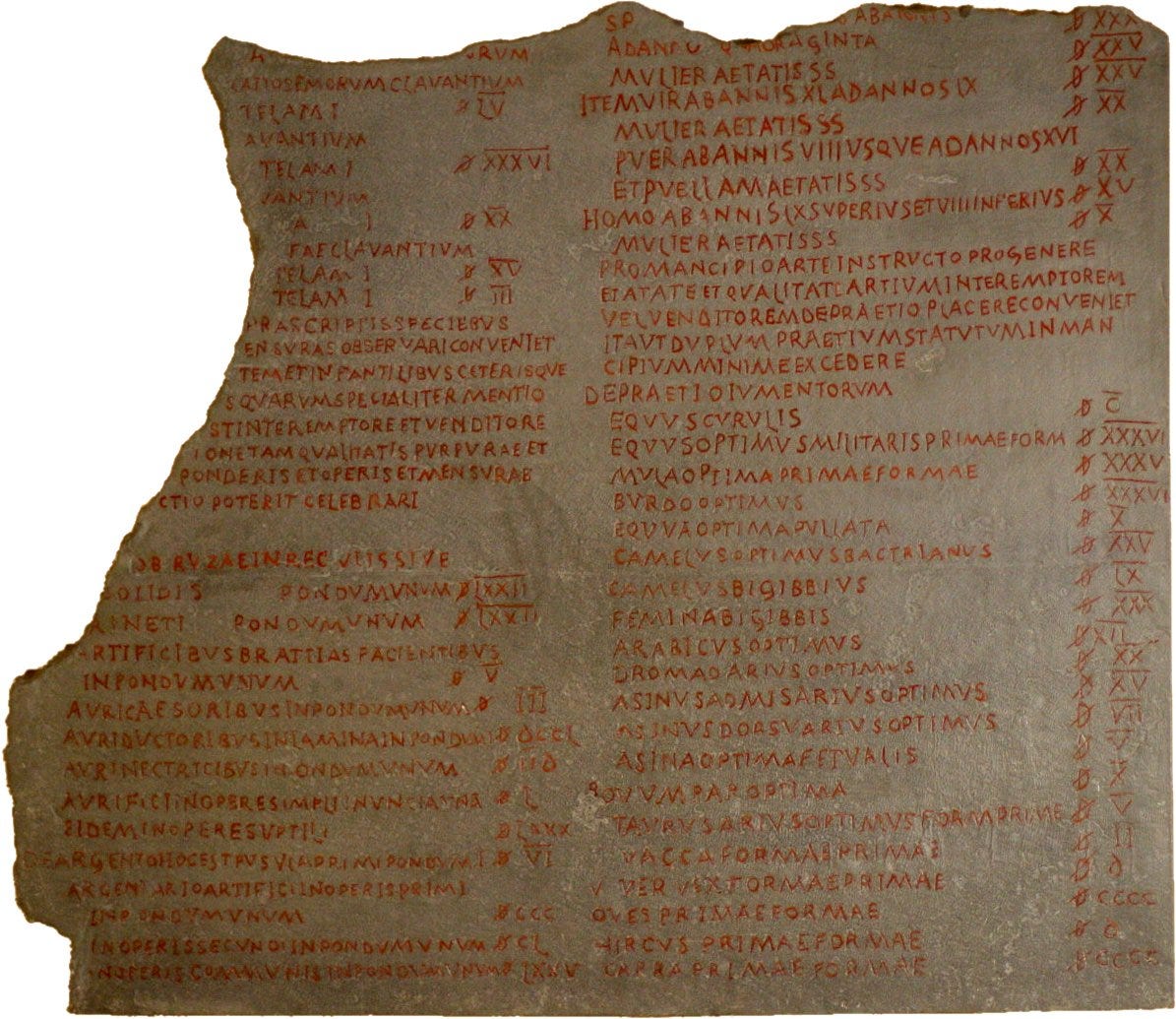

Perhaps the worst part of it is that rent control and its subsequent failure is not a new phenomenon. History is littered with examples of well-intentioned but misguided attempts to control prices, dating back to ancient civilizations. In 301 AD, Roman Emperor Diocletian issued the Edict on Maximum Prices, which set strict limits on the prices of goods and services throughout the empire. The results were as predictable as they were disastrous. The Roman author Lactantius, in his work "De Mortibus Persecutorum" (On the Deaths of the Persecutors), describes the aftermath of Diocletian's edict: “Scarcity became more excessive and grievous than ever, until, in the end, the ordinance, after having proved destructive to multitudes, was from mere necessity abrogated.”

Why Doesn’t it Stop?

Why, in the face of overwhelming evidence and historical precedent, do we keep enacting rent control policies? The answer, according to Thomas Sowell's Basic Economics, lies in the political calculus that drives decision-making:

Politically, rent control is often a big success, however many serious economic and social problems it creates. Politicians know that there are always more tenants than landlords and more people who do not understand economics than people who do. That makes rent control laws something likely to lead to a net increase in votes for politicians who pass rent control laws.

We, as a society, need to be able to get this right. It is not enough for these ideas to be only discussed in academic circles. This knowledge needs to permeate our public consciousness. It needs to become part of the fabric of our political discourse, not just a fun fact that students memorize for an exam and then promptly forget.

The Persistence of Zombie Ideas

The phenomenon of zombie ideas—concepts that persist despite being thoroughly debunked by evidence—is not limited to the field of economics. Another prime example is the DARE (Drug Abuse Resistance Education) program that was ubiquitous in American schools. The program aimed to prevent drug use among youth by teaching them that drugs were bad.

Despite its noble intentions and widespread adoption, the effectiveness of DARE has been repeatedly shown to be lacking. The program's Wikipedia page cites eight studies that evaluated its impact, with some finding no effect and the majority concluding that DARE was actually counterproductive—that is, it led to an increase in drug and alcohol use among participants. Yet, despite mounting evidence of its ineffectiveness, DARE persisted for years.

Zombie ideas that refuse to die are pervasive in our society. Two more examples that come to mind are the belief that vaccines cause autism and the unsubstantiated fear of genetically modified organisms (GMOs). Both of these notions have been extensively debunked by scientific research, yet they continue to persist in the public consciousness.

Conclusion

My understanding is that DARE has been wound down, but this is just one example where, after 30 years, evidence finally won out. (Actually, before I say that, I should inquire about what replaced it. I wouldn’t be surprised if it’s the same idea under a different name.) Either way, it doesn’t seem like strong enough evidence to suggest we’re getting better at this. Ideas that are intuitive but don’t work can be impervious to evidence.

In Paul Krugman’s post on rent control that I mentioned earlier, he goes on to say:

None of this says that ending rent control is an easy decision. Still, surely it is worth knowing that the pathologies of San Francisco's housing market are right out of the textbook, that they are exactly what supply-and-demand analysis predicts.

But people literally don't want to know. A few months ago, when a San Francisco official proposed a study of the city's housing crisis, there was a firestorm of opposition from tenant-advocacy groups. They argued that even to study the situation was a step on the road to ending rent control—and they may well have been right, because studying the issue might lead to a recognition of the obvious.

So now you know why economists are useless: when they actually do understand something, people don't want to hear about it.

In the end, crafting effective public policy requires more than just good intentions; it demands seeking the truth and a willingness to confront hard realities. Ending rent control would not be easy, but recognizing its failures is a necessary step toward creating policies that genuinely help those in need. Hopefully we can look past the superficial appeal of intuitive but ultimately flawed solutions and instead rely on evidence-based policies.