Broaching such a topic can be dangerous territory. Reeves says he “lost count” of the number of people who advised against it. Critics accused him of reinforcing biological essentialism by emphasizing sex differences or detracting from women’s rights by talking about men. This book surely took fortitude to write, and I’m glad he did.

That said, while Reeves’ evidence is compelling, I found myself often disagreeing with his prescriptions. He acknowledges biological differences between the sexes, yet too often treats the resulting disparities as problems requiring intervention. His solutions lean heavily on top-down mandates and quotas, attempting to engineer specific outcomes rather than focusing on individual flourishing. Reeves diagnoses real problems, but he often defers to a gap-closing creed that seems designed to satisfy a spreadsheet warden obsessed with balanced columns, not individual well-being.

The State of Boys and Men

Reeves marshals extensive data to paint a troubling picture. By nearly every educational measure, boys are falling behind. The most common grade for girls is now an A; for boys, it's a B. Boys are 50 percent more likely than girls to fail at math, reading, and science. In the UK, 40 percent of women enter college at age 18, compared to just 29 percent of men. In the US, women now earn 100 bachelor's degrees for every 74 earned by men.

Below are a couple of particularly telling graphs from the book:

He points to lots of reasons why boys and men aren’t doing well. His central observation is that men have traditionally derived meaning from their role as providers, but this foundation has eroded as women's economic independence has grown. The result is a crisis of purpose that touches every aspect of men's lives. He says men are “increasingly unable to fulfill the traditional breadwinner role but yet to step into a new one.”

Differences Between Men and Women

Reeves and I share considerable common ground. We both recognize that nature and nurture matter and interact in complex ways to create differences between males and females. Sex differences are influenced by cultural context—societal norms can either amplify or suppress biological tendencies.

Reeves even lists some biological differences between men and women. He observes that "men are typically more aggressive, take more risks, and have a higher sex drive than girls and women." He notes that "males are a bit more interested in things, while women are a bit more interested in people," and emphasizes that "men have a greater appetite for risk. This is not a social construct. It can be identified in every known society throughout history."

He also points to developmental differences, noting that boys' brains develop more slowly than girls', with the male prefrontal cortex particularly lagging behind. These differences persist beyond adolescence and, as Reeves acknowledges, have societal implications: "Masculine traits are more useful in some contexts, and feminine ones in others."

I appreciate Reeves' empirical approach to these questions. The existence of sex differences is ultimately an empirical question, not one of ideology, and he treats it as such. He is, of course, aware of the political sensitivity of the topic, noting that "The idea that there is a natural basis for sex differences is, however, politically charged. So I'd better get the caveats in right away. First, while certain traits are more associated with one sex than the other, the distributions overlap, especially among adults."

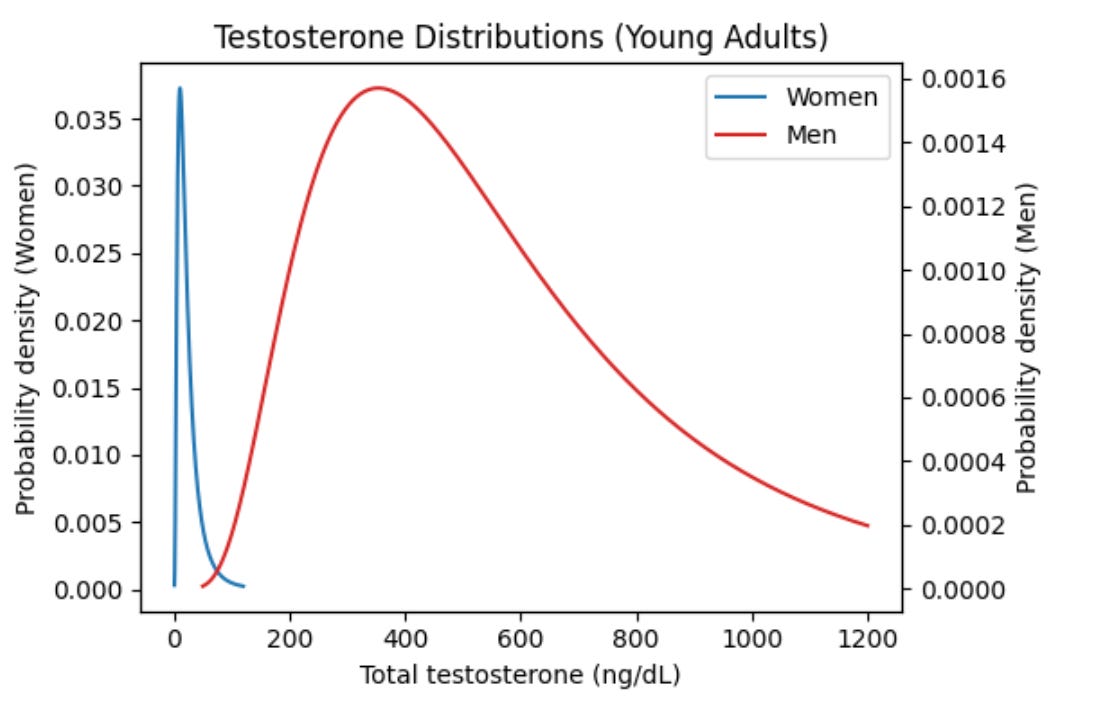

Reeves relies on this notion of overlapping distributions to justify many of his policy claims, so it’s worth exploring. While technically accurate, it obscures the magnitude of differences. We hear this concept invoked frequently to downplay differences between groups, but the goal should be to understand the magnitude first, and then we can decide what we think about it. Let’s look at one of those overlapping distributions to get a sense of it.

This is a graph of testosterone. Technically, there is an overlap. Technically, some women have more testosterone than some men, but using these distributions1, a man in the bottom 1% of men still has more testosterone than 99% of women, and vice versa. The average man has about 27 times as much testosterone as the average woman, and more testosterone than 99.999% of women. So when someone says “overlapping distributions”, it’s worth asking what those distributions look like.

Admittedly, testosterone is one of the least overlapping differences between men and women, but it’s an important one. We think of it as the muscle-building hormone, but it does much more than that. Low testosterone in men is associated with poor cognitive performance, higher rates of depression, and higher risk of Alzheimer’s2, though the impacts on women appear to be less significant. It also seems to contribute to males’ greater interest in sports. Women with much higher rates of testosterone due to congenital adrenal hyperplasia also display much greater interest in sports. Sometimes it’s hard to get the feel of what these effects mean, so I recommend reading one woman’s experience taking testosterone replacement therapy. This is, of course, anecdotal, but it gives you a visceral sense of how significant hormones are to our lives.

When Reeves invokes "overlapping distributions" without showing the actual data—without revealing that the overlap in testosterone is vanishingly small—he minimizes a biological reality that fundamentally influences behavior. It’s important to look at these numbers and acknowledge that some sex differences are so pronounced they can be more accurately thought of as categorical differences rather than swept away due to a tiny amount of overlap.

Reeves’ Solutions

Reeves advocates for starting boys in school a year later than girls (which he calls "redshirting," borrowing from the sports term), recruiting more men into healthcare, education, administration, and literacy jobs (HEAL—a term I think he coined), and providing more support to keep fathers involved in their children's lives.

Within each topic, he offers a lot of ideas, so some I agreed with and some I didn’t. But my fundamental disagreement lies with his consistently top-down approach. Often, when Reeves sees a gap between the sexes, his reflex is to declare, "we must close or at least shrink this gap." Throughout the book, I found myself repeatedly asking: Why? Why must we mandate these outcomes? Why assume every disparity requires policy interventions?

I think this “closing the gaps” instinct is just fundamentally flawed.

For example, he says we have an “education system favoring girls and a labor market favoring men” and that “We need to fix both”. His main evidence that schooling favors girls is that they do so much better at it—higher GPAs, higher college‐entry and completion rates.

Let’s take the going to college part. We can think of whether people go to college as a function of whether they have the opportunity and whether they find the opportunity valuable enough to justify the costs (both financial and opportunity costs).

Higher female enrollment isn't obviously a question of opportunity. There are some women-only scholarships, but I doubt it’s a large effect. And it’s not like we live in a culture where parents routinely fund daughters' educations but not that of their sons. If we did, that would clearly be a problem worth addressing. But that's not our reality.

Instead, it could be a question of value. If 10 million women decide college serves their best interests, why must exactly 10 million men reach the same conclusion? Why would men and women necessarily derive identical value from our education system? Reeves acknowledges biological and psychological differences between the sexes, yet resists accepting that these gaps might be producing the differences we see.3

My point isn’t that the current gaps are necessarily “correct”, but to push against this knee-jerk reaction to close every gap, to form people to fit the spreadsheet ideal.

Here’s another example: there is plenty of evidence that men are more interested in computer science and women in psychology (Reeves even cites some of it). Imagine this was the only difference between men and women. Since jobs in computer science require less formal education than ones in psychology, this would create a college enrollment gap. Obviously, the difference between men and women extends beyond college degree preferences, but my point is, there are many reasons this gap could exist. Why is there some moral mandate to close it?

I want everyone who would benefit from going to college to have the opportunity. But if everyone gets that opportunity and we still see a gap, I see no cause for concern. Equal opportunity, not equal headcounts, should be the goal.

Let me give another example of why “closing the gaps” is fundamentally the wrong way to approach public policy. Men have much higher suicide rates than women. But I don’t want to “close the gap”. I want to lower both rates. If your mission is to reduce suicide rates for females, I applaud you. I think dedicating oneself to reducing female suicide rates is a great and wonderful thing to do, irrespective of any gaps. Yes, it would be great if we could lower the suicide rate for males as well. But “closing the gap” shouldn’t be our lodestar—maximizing flourishing and minimizing suffering should be.

Obviously, Reeves isn't advocating for increasing female suicide rates. But societies become slaves to their metrics—what gets measured gets optimized, even at the cost of real human goals. A gap between demographic groups should serve as a starting point for investigation, prompting us to ask: "Is something going on here?" Yet the mere existence of a gap doesn't prove a problem exists. Too often, we leap from observing a disparity to demanding intervention, without pausing to determine whether anyone is actually being harmed or excluded.

That’s the disagreement at a philosophical level. Let’s take Reeves’ proposals in turn.

Contra Redshirting the Boys

Reeves points to the slower developmental time for boys and proposes that boys should start school a year later by default—attending pre-K for two years while girls attend for one. I hadn’t heard this proposed before and I found it genuinely innovative and somewhat radical. Kudos to him for thinking boldly.

However, it also epitomizes the problem I have with his top-down mentality. I am perfectly willing to accept that many children benefit from starting school later. I am also willing to accept that perhaps boys, on average, might benefit more than girls. Though I don’t have any strong intuition about how significant this effect might be, I will accept, for the sake of argument, that boys might do best starting a full year later. I don’t know if this is true, but it’s plausible. But why mandate this based on sex?

Why not make school entry more individualized? We could develop readiness assessments (not necessarily written tests) based on developmental milestones: "Children generally thrive in first grade when they can do X, Y, and Z." This would allow natural variation while addressing developmental differences.

We could also work to decrease the stigma around starting later. Perhaps it's simply a matter of publicizing what’s already happening—according to Reeves, children from affluent households are twice as likely to delay school entry. When parents realize that wealthy families view "redshirting" as a strategic advantage rather than a developmental concern, perceptions might shift.

Why does this make a difference? Let me tell my abbreviated story with school. If my high school teachers had to give me a superlative, I would suggest “Safest to Ignore”. That is, I could be pretty much left alone in class with the textbook, and I was “fine”. “Fine,” as in, I wasn’t going to fail the class. I wasn’t going to get in a fight with the kid next to me. I was certainly not being challenged in the subjects I was best at, but schools don’t measure that. By every metric principals use to evaluate teachers, ignoring me caused no harm.

This experience is far from unique. Countless students sit bored in classes not designed for them. Under Reeves' system, I would have been a year older and even more bored.

Why not let a gap appear organically? If we normalize flexible school entry and boys naturally average a year behind girls, both Reeves and I are happy. But what if the gap is only six months? I'm still fine if this reflects individual choices and abilities, but Reeves wants more. Why? Why must the gap be exactly one year? Why impose uniformity instead of allowing variation?

Contra More Male Teachers

Reeves also advocates for recruiting more male teachers, citing studies that show boys perform better with male instructors, particularly in English, while girls perform equally well regardless of the teacher's gender. Even accepting his premises, I disagree with his approach.

Finding a correlation with gender doesn't mean gender is the causal factor. The relevant factor might be teaching style, subject background, or personality traits that happen to correlate with gender. Instead of mandating quotas, why not identify what actually drives student success and recruit teachers with those qualities? And if it turns out that we can’t determine a priori which teachers will be better, we could at least work harder to retain the best ones.

Reeves claims boys do best with male teachers and black children with black teachers, while other students are unaffected. If true, a merit-based system would naturally produce these outcomes. But what matters is building systems that identify, hire, and especially retain excellent teachers. If the best teachers turn out to be 80% black men and all children flourish, wonderful. The goal is to identify what makes teachers effective and select for that directly—not to use demographics as a crude proxy for teaching excellence. If the distinguishing qualities aren't demographic at all, we'd discover that too.4

Contra More Men in HEAL

Reeves wants more men in health, education, administration, and literacy (HEAL) fields. He notes the low male representation in these jobs and the stigma surrounding men in caregiving roles and wants to change that. Drawing parallels to efforts to increase women in STEM, he proposes similar initiatives for men in HEAL, setting specific targets: 30 percent of STEM jobs for women, 30 percent of HEAL jobs for men by 2030.

What's Reeves' justification? He points to overlapping distributions, arguing it's "absurd to think that the 18% male share of social workers is an authentic representation of the true level of interest in the job among men." But the simple fact that men's and women's attributes overlap doesn't justify any particular numerical target. The existence of overlap tells us nothing about what the "right" percentage should be. Why 30 percent? Why not 25 or 35?

Here, he cites the work of psychologists Rong Su and James Rounds5, who found that differences in interests between men and women strongly influence career choices. These studies don't attempt to separate what’s cultural from what’s biological or resolve any “nature vs nurture” debates. They simply document current interests. For example, they find that men show much higher interest in engineering than women, with a Cohen’s d of 1.11, which indicates a large effect size6. Then, they examine who falls in the top 10% of interest for various subjects and use that to predict gender ratios within each field.

Yet Reeves takes this descriptive research and transforms it into a prescriptive mandate. While the studies show that differences in interest contribute to gender disparities, they can’t be used to calculate the "correct" percentage of women or men in any field.

Reeves, however, uses this data to conclude that we need more women in STEM. Funnily enough, if you look at the graph in the academic paper, it projects fewer women in applied mathematics than the actual amount (note that applied mathematics is distinct from mathematics; Reeves omits this column from his chart). Following this line of thinking, should we have fewer women in applied mathematics? No, of course not. This kind of academic overreach is silly.

For me, the question is: Are there large numbers of women in HEAL wishing they were in STEM, and men in STEM yearning for HEAL careers? Perhaps some people were discouraged from pursuing those fields when, in fact, they would have loved them. If so, I support those people changing careers. But the mere existence of gender disparities doesn't prove this.

If everyone got the job they wanted and we still had more women in HEAL and more men in STEM, would that be a problem? Who exactly is harmed by these gaps? What actual human being suffers? On what grounds is there a moral imperative for intervention?

Regarding reducing stigma, we are more aligned. He relates a story where his son was turned down for a childcare job because “the parents were uncomfortable leaving their children with a man.” I think the fact that we have gotten to the point of discomfort with the idea of men being around children is a blight upon our society.

Here, I think we can and should do things. To some degree, we can change what things we as a culture do and do not stigmatize. In general, cultural barriers that prevent people from pursuing careers they'd excel at should be dismantled. I think we can do it in the case of reducing stigma. Activist organizations have been successful here. Recall, for example, the success of MADD in stigmatizing drunk driving, or the success of reducing negative stigma against the LGBT community.

Reeves on Career and Technical Education

Reeves also writes on the importance of Career and Technical Education (CTE), and I appreciate his thorough compilation of the data. I largely agree with his emphasis on providing alternative pathways to four-year degrees. We both recognize that our society treats college as inherently virtuous and non-college paths as somehow lesser. This cultural bias pushes some people into expensive degrees they don't need at the cost of more valuable job training.

But here's where Reeves confuses me: He rightly criticizes our college-for-all culture, yet simultaneously wrings his hands over the fact that more women than men attend college. If we truly believe that college isn't necessary for everyone—and that many people would be better served by vocational training or direct entry into the workforce—then we should stop treating the gender gap in college attendance as such a big deal. The very act of declaring "This is bad for men and we need to fix it" reinforces the notion that college attendance is an important measure of success.

A Better Path Forward

Where Reeves and I agree: Culture matters enormously in shaping how biological predispositions manifest. It is good for people to understand that sex differences exist and that there is some degree of overlap. Most importantly, we should shout from the rooftops that every person is an individual and shouldn't be judged by group averages. We should eliminate genuine discrimination and work to ensure everyone can pursue their potential.

Where we diverge: I don't want to "close gaps" for their own sake. I want to lower suicide rates for both sexes, not celebrate if male and female rates converge. I want excellent teachers, regardless of whether they're disproportionately male or female. I want a society that works with people as they are, not one that hammers them into something else for the sake of balancing a spreadsheet.

We stand on the brink of an AI revolution that is likely to upend the labor market faster than any transition we’ve seen before. We’re going to make a lot of impactful decisions in the coming decade, and we need to be carefully focused on creating human flourishing, not optimizing for bureaucratic spreadsheet equality. We need an approach that values human flourishing over statistical tidiness.

Reeves asks important questions about boys and men. But his answers, constrained by a focus on stamping out spreadsheet disparities, would create a world where individual talents and choices matter less than satisfying some bureaucratic checkbox. We should do better. The future depends not on achieving perfect statistical parity, but on creating a society where everyone—male and female—can pursue their potential without artificial barriers or forced outcomes.

The real tragedy isn't that men and women might sort into different fields or achieve different outcomes. It's that in our obsession with closing gaps, we risk creating a world where no one gets to be who they truly are.

These distributions represent typical testosterone levels in healthy adults. Medical conditions can cause dramatic exceptions—for instance, women with androgen-secreting tumors may have testosterone levels exceeding 1,000 ng/dL, well above the male average. Similarly, men with certain conditions can have abnormally low levels. However, these medical cases are rare and don't affect the overall pattern of minimal overlap between male and female testosterone distributions in the general population.

These may not be causal relationships. My point here isn’t to get into the literature on testosterone, but merely to highlight that its impacts are significant.

He does cite the paper “Heterogeneous returns to college over the life course“, which is an important contribution to the topic, but doesn’t address my point about degree and job sector differences.

From a practical perspective, this would require taking on the teachers’ unions. I’m going to separate out practical political difficulties.

Cohen’s d is a standardized term to compare effect sizes across different fields. To give some context, the effect of antidepressants beyond placebos is 0.30 (small effect). The difference in height between men and women has a Cohen’s d of around 1.7 (large effect). So the tendency of male interest towards engineering is in between these two.

Agreed.

I am not as familiar with Richard Reeves writing as you are, but he seems to just be reversing the old “we must close the gender/race gap” rhetoric that has failed over the last 60 years.

Boys do not want to be portrayed as victims needing compassion. And there is no reason to expect equal outcomes between genders.

Individuals are biologically different and those differences are not random for each group. Those differences lead to differing skills and preferences. Differing preferences lead to different life choices, and differing life choices and skills lead to very differing outcomes.

I think girls are doing better in education because girls tend to be higher in what psychologists call “Agreeableness” (i.e. they are more likely to do what they are told). I think the old narrative that the way to succeed is “go to college” is falling apart and boys are catching on quicker than girls are.

And particularly trying to get boys to go into the “caring professions” is terrible advice. Boys in college naturally prefer STEM, business, or economics and that is a good thing. The majority of college majors that girls choose are not really viable job skills. They are mainly credentials for a desk job in a different field.

Sending boys to school a year early will likely accomplish nothing and may do more harm than good. Most boys hate sitting still and listening to adults for hours in end.

I do agree with you and Reeves that we need more non-college vocational schooling and boys will likely benefit from that more.