This post explores the relationship between money and happiness. While happiness research remains a complex and debated topic, it has produced some robust and consistent findings. Our aim is to highlight these findings and understand what they tell us about money and happiness.

Happiness research suffers from many problems, not the least of which is the difficulty in clarifying what it is we actually aim to study. Though the specific terminology varies, in general, most happiness research distinguishes between two forms of happiness: hedonic, which pertains to day-to-day pleasure or immediate gratification, and eudaimonic, which relates to a deeper sense of purpose or fulfillment. Hedonic happiness might be the joy you feel enjoying a favorite meal, while eudaimonic happiness is more about the satisfaction from achieving a personal milestone or finding a deep sense of fulfillment. Although this distinction is not perfect, it provides a useful framework for understanding the nuances of human well-being.

Measuring happiness inevitably encounters challenges. The term "happiness" itself is nebulous—what does it signify, and how is it interpreted across different languages? To circumvent these complexities, researchers employ "self-anchoring" questions that do not rely on specific definitions of hard-to-define words. A widely used method is the "Cantril Self-Anchoring Scale," or "Cantril Ladder," devised by psychologist Hadley Cantril. This approach involves asking participants the following question:

Please imagine a ladder with steps numbered from zero at the bottom to 10 at the top. The top of the ladder represents the best possible life for you and the bottom of the ladder represents the worst possible life for you. On which step of the ladder would you say you personally feel you stand at this time?

This style of questioning is advantageous because it circumvents the task of precisely defining “happiness.” But it still runs into the same problem that afflicts all subjective measurements—it’s all relative, and, even worse, you might not even know what it’s relative to. No matter how you do it, people are going to use their environment and experiences as reference points. Do they think of the top rung as the happiest person in the world? Happiest they know? Or know of? Do they include fictional characters? Did they spend their 20s studying philosophy and imagine impractical scenarios like infinite bliss (or, at the bottom rung, infinite torture)?

This especially becomes a problem when you compare people across time. Why would you complain about the need to venture into the freezing rain at night to reach an outhouse, with its barrage of unpleasant smells, when the only alternative you can imagine is living with those odors inside your home. Thus, we should be especially wary of happiness measures across time.

In any research field, while there's a lot of noise, there are also valuable signals to be found. So, with the above caveats in mind, we can still focus on identifying broad, significant trends rather than getting lost in minor variations.

There are three robust findings regarding the relationship between money and happiness that stand out:

1. Individual Income and Happiness: There's a real, albeit modest, positive effect of personal income on happiness.

2. National Wealth and Happiness: Countries with greater wealth report greater happiness

3. Wealth Over Time and Happiness: Despite increasing wealth over time, Americans’ happiness levels have not risen.

That is, although people and countries with higher incomes tend to report greater happiness, happiness levels in the US have not risen despite rising incomes. These statements seem to be in conflict, but we’ll get to that later.

Individual Happiness Rises with Income

Does money buy happiness? This question is at the heart of a landmark 2010 study by Daniel Kahneman and Angus Deaton, which investigates how income influences happiness. In this paper, they studied both hedonia, which they called ‘emotional well-being’, and eudaimonia, which they called, ‘life evaluation,’ and measured using the Cantril Ladder. They discovered that while life evaluation consistently increases with higher incomes, emotional well-being improves up to an annual income of about $75,000—equivalent to roughly $106,000 in today’s dollars. They claim that after this threshold, additional income does not lead to greater day-to-day happiness. Kahneman and Deaton summarize their findings by stating, “We conclude that high income buys life satisfaction but not happiness, and that low income is associated both with low life evaluation and low emotional well-being.”

Unfortunately, the nuanced findings of Kahneman and Deaton's study, which reveal strong correlations between income and various dimensions of happiness, were largely overshadowed by the public and media's focus on one specific outcome: the absence of a correlation between income above $75,000 and hedonia. This particular detail captivated public interest and was broadly reported, leading to the widely accepted yet oversimplified belief that 'money doesn’t buy happiness.' Such a narrative, while catchy, overlooks a crucial aspect of the study's results—that higher income significantly contributes to life satisfaction.

Not only does the narrative get most of the study wrong, but the part that it does get right seems to be wrong. In 2021, Matthew Killingsworth challenged Kahneman and Deaton's conclusion with a new study. Using a larger and more accurate dataset (see the paper for details), he found that happiness doesn't plateau at $75,000. Instead, all measures of happiness continue to rise linearly with the logarithm of income and show no signs of stopping.

Faced with these conflicting results, the lead authors from the two conflicting papers—Kahneman and Killingsworth—decided to collaborate directly in what's known as an adversarial collaboration, where researchers with differing viewpoints work together to find common ground. They reviewed both studies together and found both to be valid, yet with differing results.

So they produced a new study aimed at digging deeper into the disagreement, and, happily, they resolved their conflict: happiness indeed increases with additional income. Yet, there's an exception. For the least happy 20% of the population, their sense of happiness levels off when income hits around $120,000. This exception aside, for the majority of people, both measures of happiness—emotional well-being and life satisfaction—continue to rise with income.

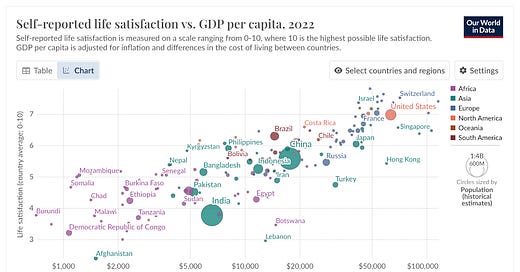

Happiness Rises with Income at the Country Level

The next point to make is that happiness rises with wealth at the national level as well. This is, again, hardly a surprise, but it’s worth making clear how robust this finding is. It not only reaffirms the link between economic prosperity and overall well-being but also offers insight into how nations can improve the happiness of their citizens.

There are no countries that have a per capita GDP less than $5,000 and a life satisfaction above 6. There is only one country, Hong Kong, with a per capita GDP above $50,000 and a life satisfaction below 6. This anomaly is probably because, in the years leading up to the survey, Hong Kong had had its largest protest erupt and subsequently quelled by the Chinese government. But the overall message is clear from this graph: Wealth is an important component to greater life satisfaction and, again, there is no indication in the data that this stops at a certain level.

As the US Has Gotten Wealthier Over Time, People Have Not Gotten Happier

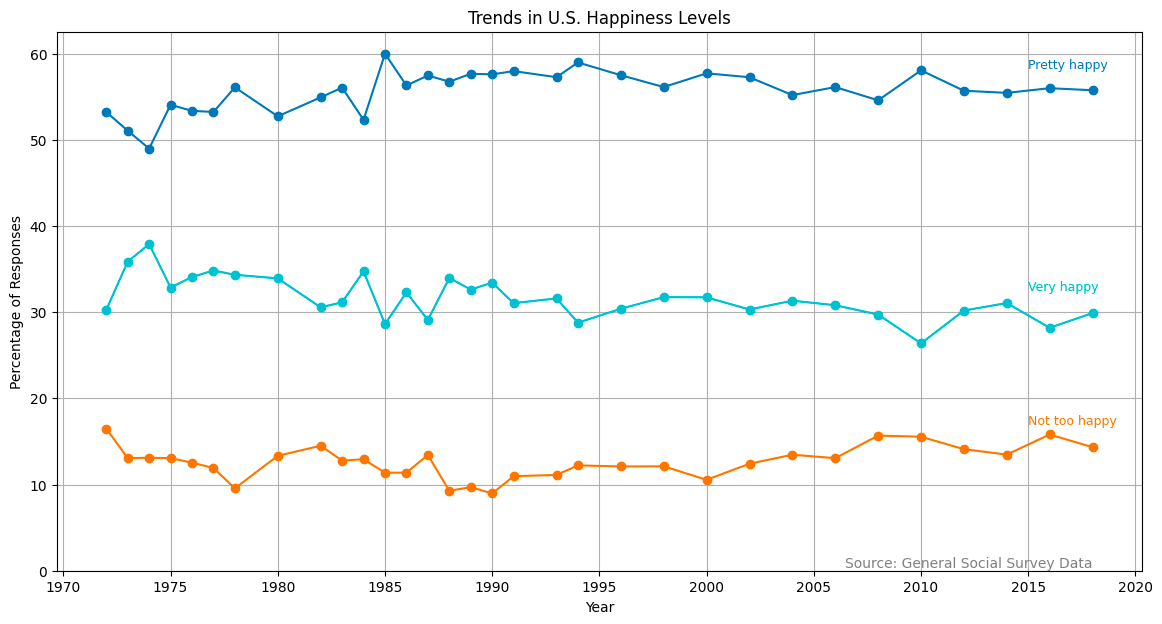

Lastly, let’s look at how happiness changes over time. We’ll use data from the General Social Survey (GSS), which is a sociological survey created and regularly collected since 1972 by the University of Chicago. It gathers data on the United States' societal structure and trends, including national institutions, attitudes toward politics, moral values, family dynamics, economic status, and health. By employing a standardized questionnaire, the survey aims to provide a comprehensive longitudinal picture of how the attitudes and behaviors of the American public change over time.

They asked the following question: “Taken all together, how would you say things are these days—would you say that you are very happy, pretty happy, or not too happy?” Here are the results:

As you can see, the scores are pretty steady over time. Instead of trying to focus on three lines, it’s easier to see if the data are combined into one. In the figure below, I’ve combined them into a happiness score by giving 1 point for everyone who said they were “very happy”, 0.5 points for everyone who said they were “pretty happy”, and 0 points for everyone who said they were “not too happy.” Here’s what that looks like:

We can see pretty clearly that it doesn’t change much, an astounding finding given the dramatic changes in other aspects of life. We can add per capita GDP to this graph to see how they relate.

Looking only at this graph, I would say there is approximately no relationship between wealth and happiness.

Point 2 (from the original three points) was that countries with more wealth report being happier. Point 3 shows that people do not necessarily get happier as they become wealthier over time. That is, the correlation between money and happiness exists at a single point in time—the richer people are happier than the poorer people. But it does not hold over time—if you have a bunch of poor people and make them rich, they do not become happier. We seem to have found a paradox.

This apparent paradox is not a new observation. It is known as the Easterlin Paradox and was first formulated by economist Richard Easterlin in 1974. The graph above, which is almost entirely built upon data since the paradox was first noted, only strengthens the evidence. You can see the same thing in older data as well, such as this graph showing steady subjective well-being in the US since the end of World War II.

Critics might object to this conclusion by noting that inequality has also risen in the US, so perhaps all the money went to the top. We can easily check this by examining the median income instead, which would remain stagnant if only the wealthy benefited from growth. Again, using inflation-adjusted figures, we find that the data tells the same story.

There is plenty to discuss about these results, including Easterlin’s Paradox, but that’s for another post. The goal of this post was only to explore three key insights about the relationship between money and happiness: higher personal income correlates with greater happiness, wealthier countries report higher levels of satisfaction, and yet, in the U.S., increased wealth over time hasn't boosted happiness levels.

Yep, but it leaves us with the puzzle of Americans with more money, but not more happiness.