There is an “approved narrative” in climate change journalism that most stories adhere to. It goes something like this: Every change in the climate is bad, new climate information shows it’s worse than we had realized, and the Earth is in a crisis, but we can still act now to prevent it.

This is, obviously, a broad generalization, and there are certainly counter-examples that contradict it. However, when we examine the climate media landscape as a whole, it becomes clear that there is a prevailing narrative that is consistently reinforced. Unfortunately, this narrative has resulted in a misrepresentation of climate data, as it is often forced to conform to this predetermined perspective.

It’s Always Bad

The first thing to know about climate news is that it must be bad. But this doesn’t make sense—how could such a complex, global phenomenon only produce bad events? At the very least, if the globe is getting warmer, then people are going to spend less in the winter to heat their houses. That seems indisputable and significant but is never discussed. Also, fewer people would die from extreme cold, which is significant because more people die from cold than from heat.

Another thing that seems pretty obvious is that some crop growth is going to increase as there is more carbon in the atmosphere. Greenhouses often pump in more CO2 to increase plant growth. Why? Because plants require CO2 in the air to grow, so the more they can get, the more they grow, up to a point. Although the amount of carbon in the air is increasing, it’s still a tiny fraction of the atmosphere. The air around us is about 99% nitrogen and oxygen, about 0.9% argon, and the last 0.1% is everything else. CO2 is just 0.04% of the atmosphere, or the infamous 400 parts per million. Research suggests plants reach their optimal growth at about 1,200 PPM. There are other limiting factors and effects involved in plant growth, but I think we should acknowledge that, all other things being equal, plants would prefer a globe with more carbon rather than less.

But these facts don’t make it into the approved climate narrative. It feels like one can’t even acknowledge basic facts without fear of being called a “climate denier.” Even after writing the above paragraph, I’m rushing to get to the part where I say that none of this suggests that the benefits aren’t outweighed by the costs, just that there are some benefits.

And (Somehow) Always Getting Worse

That’s the baseline—it’s all bad. And yet, somehow wherever there’s new information, it’s always that climate change is worse than previously thought. If our models are decently free of systematic errors, shouldn’t the reality be better than the prediction about half the time? I’m guessing it is, but these stories never make it into the media.

Part of this is due to the difficulty of reporting climate change any other way. Reporting is on events and climate doesn’t cause events, only weather does. There are plenty of beautiful days, but those aren’t “weather events”.

All that’s left to report is on non-events, and this isn’t nearly as gripping. It would be like reporting on airplanes that didn’t crash. There could be studies of trends over time, but it would be hard for these to make headlines.

While I will admit that’s part of the reason, I don’t think it explains everything. I think there is still a bias toward the approved narrative of news that must be bad and getting worse. For example, how would it be reported if a study showed that climate change was lessening the impact of some terrible natural disaster? Choose any—earthquakes, floods, etc.—I just can’t imagine the headline “Scientists say climate change reduces the severity of earthquakes, saving thousands of lives.”

Possibly Misleading Framing in Scientific Studies

I wonder if some of it goes back to the scientists as well. I’ve even found what I consider somewhat misleading framing of climate topics. For example, the 2019 Special Report on the Ocean and Cryosphere in a Changing Climate stated that “There is emerging evidence for an increase in annual global proportion of Category 4 or 5 tropical cyclones in recent decades (low confidence).”

When you think about it, that’s an odd phrase. Why do they focus on the proportion? The proportion is the number of high-intensity hurricanes divided by the sum of the number of high-intensity hurricanes and the number of low-intensity hurricanes (or, more simply, all hurricanes). Doesn’t that seem like an odd metric to use? If we substituted in the expanded version, the sentence would become “There is emerging evidence for an increase in the number of high-intensity hurricanes divided by the total number of hurricanes (low confidence).”

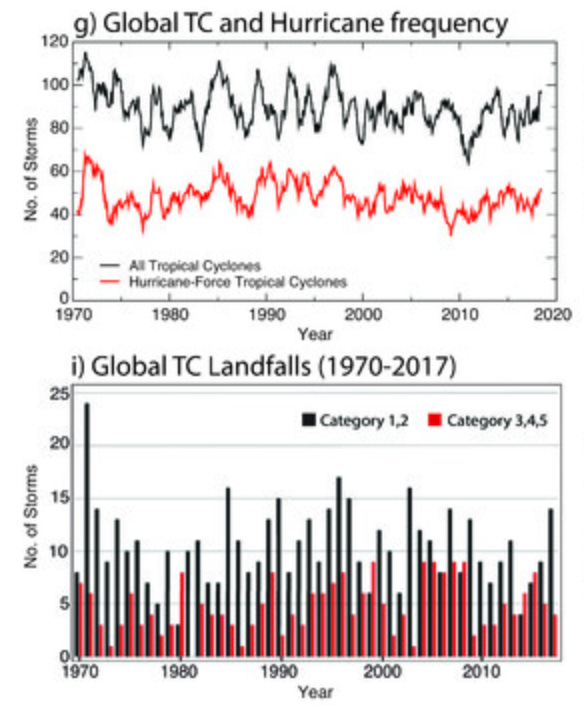

When you read it like that, your response might be “Why are you dividing by the number of hurricanes? If the frequency of high-intensity hurricanes is increasing, just tell me.” But as we can see from a graph of Global Tropical Cyclone and Hurricane frequency from this 2019 paper below, there’s no obvious trend in the frequency of major hurricanes.

If we look at future projections, we see evidence that the frequency of global hurricanes is decreasing. Let’s look at projections for tropical cyclone frequency from a 2020 assessment.

Looking at these charts, do you see evidence that the proportion of more intense hurricanes will increase? Yes, because the numerator—the number of very intense hurricanes (second graph)—stays the same and the denominator—the total number of hurricanes (first graph)—goes down. So the proportion of high-intensity hurricanes increases, which sounds alarming, but the actual number of high-intensity hurricanes doesn’t increase.

I’m not sure why it’s reported this way. Possibly it’s because some studies have suggested that the stronger hurricanes are getting stronger and the weaker ones weaker, leading to a more bimodal distribution. So maybe the authors thought it made sense to talk about the proportion? The ungenerous explanation is that it’s because the signal around high-intensity hurricanes becoming more common is weak, and the signal around low-intensity hurricanes becoming less common is stronger, so dividing one over the other makes an alarming statement sound fairly strong.

The Earth Is in a Crisis

The approved narrative isn’t created by politicians, the media, or some secret council. Like many things, it’s the result of different organizations with different interests acting in accordance with their own incentives. You can see how the narrative of spreading fear and the threat of imminent danger from climate change spreads in a story that went viral recently. It was the claim that the world will end in 12 years, which (as far as I know) was originally said by Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (to loud applause from a live audience). A politician saying something wildly inaccurate would hardly be new, but the media response is illuminating. The Washington Post responded with the headline Ocasio-Cortez says the world will end in 12 years. She is absolutely right. The BBC said 12 years to save the planet? Make that 18 months. Hopefully, I don’t need to say this, but she is absolutely wrong. This is total nonsense. This is more wrong than saying that the climate is not changing. The New York Times, fortunately, was more mixed in their headline: Do We Really Have Only 12 Years to Avoid Climate Disaster? (Subtitle: The widely recited “12-year deadline” is wrong — and right). In all of these, the pieces eventually get around to admitting that the claim isn’t true. But they decided to run with those headlines anyway. It’s not that there are no truth-tellers—in this particular case, Scientific American ran a piece with the headline, “No, Climate Change Will Not End the World in 12 Years”, which was a welcome distinction.

I think because climate change has become an issue of warring tribes, these headlines are allowed by their group. It’s become their mission to scare people about climate change, and these headlines serve that purpose. When a debate becomes solidified into a Red Tribe vs Blue Tribe argument, truth is left behind when one is fighting for a cause. People are fine with the most inane justification for anything their side does. What would the defense be here? It’s OK because it’s in the opinion section? Would it be OK if the opinion headline were “Climate Change Isn’t Real”? Or maybe people shouldn’t just read the headlines? No, don’t write those headlines. Or is it that whenever their side says something wrong, it “isn’t meant to be taken literally”? This is just a post hoc excuse for being wrong, accepted when proclaimed by your tribe but never by the opposing tribe. These headlines are lies, and they shouldn’t be tolerated.

This is the type of thing that is permissible from that mindset of “We’ve got to do everything we can to convince people of the dangers of climate change”, but I think this is a problem. Consider the impact on someone who genuinely believes this. They believe they and everyone they know will die in 12 years. How would this impact a person? Would it be good for their mental health? Or has the media taken its mission of alarming people about climate change too far?

We have some of the most famous politicians on the left saying this. Just like for years we had politicians on the right saying it’s not happening. What if people actually believe the things the media tells them? It would be awful. Why go to college if the world is going to end in 12 years? Are they going to dismiss these statements? Or do they wake up each morning feeling doomed? I find these headlines objectionable, especially in light of a Lancet survey that came out in September 2021. It was a survey of 10,000 young people (ages 16-25) in ten countries. It showed that a full 56% agreed with the notion that “humanity is doomed.”

If We Act Now, We Can Stop It

Every piece has to end with, “But if we act now, we can stop it”. Those are the rules; I didn’t write them. Obviously, it’s not always the case that we still have time. Look at the rise in global average sea level as recorded by the US Global Change Research Program. What about this chart makes it look like we can stop sea levels from rising? Should we cut emissions to the 1970s when sea levels were *checks graph* rising? Or the 1930s when they were *checks graph* also rising? Tell me which year we could go back to to reverse the trend of rising sea levels. They rose before humans emitted greenhouse gases and will continue to rise whatever we do. We are, absolutely, making the problem worse by warming the world. But pretending that low-lying regions will be spared if we switch to renewables is fanciful.

Conclusion

The media has convinced themselves that by scaring people about climate change, they can make the world a better place and poke a stick at Red Tribe for denying it for so long. The thinking appears to be that any amount of excessive alarmism is morally justified because it’ll only make people more aware of the problem. I’m skeptical of anyone who will disregard facts for the good of others.

Of all tyrannies, a tyranny sincerely exercised for the good of its victims may be the most oppressive. It would be better to live under robber barons than under omnipotent moral busybodies. The robber baron’s cruelty may sometimes sleep, his cupidity may at some point be satiated; but those who torment us for our own good will torment us without end for they do so with the approval of their own conscience.

C.S. Lewis